We compare Singapore hokkien mee with KL hokkien mee

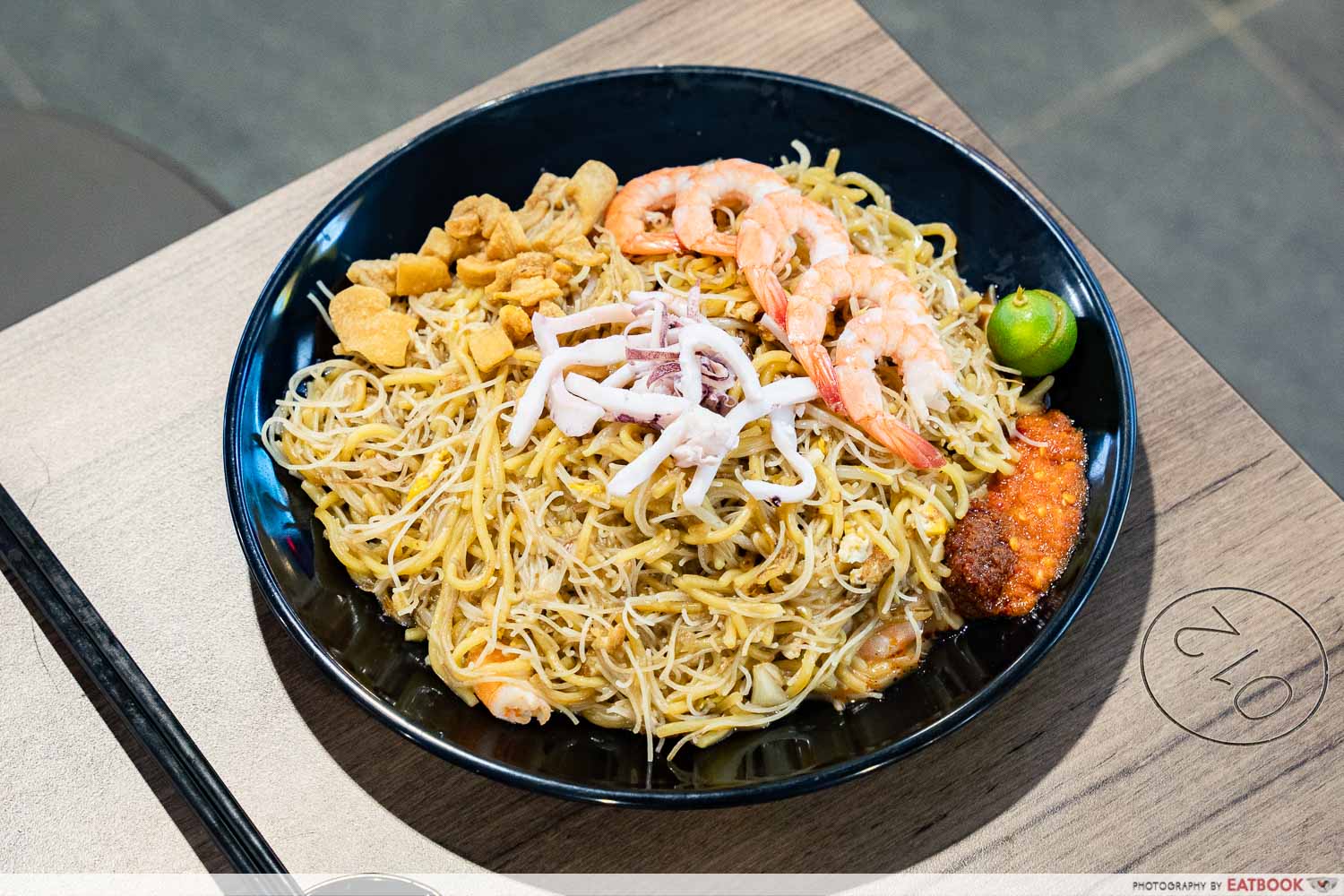

One of my favourite local hawker dishes of all time is Singapore hokkien mee. The dish is made up of thin bee hoon and thick yellow noodles, tossed in a rich stew simmered with pork bones and prawn heads. Eggs, prawns, squid, and pork belly are added to the wok, before it is topped with crispy pork lard and served with a piquant, spicy sambal.

For years, I believed that was the only correct way hokkien mee was made—that is until I was introduced to the Malaysian version. Known more commonly as KL hokkien mee, this dish appears significantly different from the Singapore-style hokkien mee I was familiar with.

Image credit: Petaling Street Charcoal Hokkien Mee

Image credit: Petaling Street Charcoal Hokkien Mee

On the most basic level, the noodles are darkened from the use of dark soy sauce, unlike its more colourful Singaporean counterpart. But beyond mere visuals, what exactly is the difference between Singapore and KL hokkien mee? Did these dishes share the same origin? How do their preparation methods differ? These are the questions I will explore in this article.

Same name, but mostly different origins

Image credit: Reagan Ong

Image credit: Reagan Ong

As it turns out, these two versions of hokkien mee sprung from different sources, with only vague influences from Fujian cuisine accounting for any similarities.

KL’s version of hokkien mee was born along Petaling Street in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, at a restaurant by the name of Kim Lian Kee. The eatery was founded in 1927 by Ong Kim Lian, an immigrant from Fujian, as noted in an article by Free Malaysia Today. According to this video by One Two Three Production, Mr. Ong initially sold a pale-coloured noodle soup dish simply named “Hokkien noodle soup”.

Though the initial dish had its moment, there was soon a demand for a more robust and savoury noodle dish. Observing that local Hokkiens liked “adding soy sauce to everything”, Mr Ong made the decision to add dark soy sauce to a stir-fried version of his original noodle dish. Thus, KL hokkien mee was born.

Singapore’s hokkien mee is also said to have been invented by an immigrant from Fujian, but it is impossible to ascertain whether it was developed from that same “Hokkien noodle soup” dish.

For starters, there are contending stories surrounding hokkien mee’s roots in Singapore. One story, recounted to us by the owner of Nam Sing Hokkien Fried Mee, claims that his father and uncle created the dish shortly after arriving in Singapore from Xiamen, China, in the 1940s.

While initially the dish was little more than stir-fried noodles and bean sprouts, they eventually added prawns and squid, forming the template for hokkien mee as we know it today. This narrative does not include a “Hokkien noodle soup” at all.

Another story, popularised by a Straits Times article from 1984, posits that the dish’s roots can be traced back to the 1880s, 50 years before KL hokkien mee was born. The article claims that an unnamed Hokkien man sold the dish along Rochor Road, before passing the recipe on to four Teochew disciples.

This eventually led to the widespread adoption of hokkien mee among Teochew hawkers, to the point where some consider hokkien mee to be an almost Teochew dish. This cross-pollination of Hokkien and Teochew cuisines meant that there was little chance the Singapore hokkien mee was going to evolve like its KL counterpart.

There’s little evidence to support the idea that the two versions of hokkien mee had a common source; on the contrary, it seems they evolved independently, shaped by the unique cultural and culinary influences of their respective milieu.

The fact that they eventually took on the same name could have been a coincidence, or part of a strange tendency to label any Hokkien-related noodle dish as hokkien mee—both Singapore and Penang’s version of prawn mee are sometimes referred to as hokkien mee as well.

Same name, but mostly different recipes

Image credit: Mr Wrong

Image credit: Mr Wrong

The two hokkien mee dishes might share a name but a lot of their other aspects differ. The most noticeable distinction lies in the broth department: while Singapore hokkien mee is prepared with an umami-rich seafood stock, the KL version makes liberal use of a starchy dark soy sauce.

Next is the type of noodle. Singapore hokkien mee sees the use of two types of rounded noodles, thin white bee hoon and thicker yellow noodles for varied textures. On the other hand, the KL version makes use of a single slightly flat, udon-like noodle type for the dish.

Image credit: Petaling Street Charcoal Hokkien Mee

Image credit: Petaling Street Charcoal Hokkien Mee

Someone who’s well acquainted with the art of frying KL hokkien mee is Lee Heng See, owner of Petaling Street Charcoal Hokkien Mee and the nephew of the dish’s inventor, Ong Kim Lian. Mr. Lee takes pride in refining his father’s recipe.

“I worked at Kim Lian Kee for about 40 years; my father taught me all I know,” he shared. Though his technique remains largely faithful to tradition, Mr. Lee claims to have improved upon it. “I cook better than my father’s one last time,” he added with a chuckle.

Image credit: Coco Ong

Image credit: Coco Ong

We asked: how is traditional KL hokkien mee made? “Fresh pork, prawn heads, and chicken bones are simmered to make the broth. We then fry the noodles with the broth, together with prawns, pork slices, pork oil and more,” Mr. Lee said. “Then, of course, lots of dark soy sauce.”

“We fry the noodles … with lots of dark soy sauce.”

On the other hand, Singapore hokkien mee focuses on perfecting the broth instead. This is confirmed by You Ri, owner of Original Simon Road Hokkien Mee, who follows a recipe that’s been around since 1960. Like most traditional versions, the dish features noodles thoroughly steeped in a rich broth made from prawns and pork bones, with the bold seafood notes standing out as its defining trait.

Though the foundation remains the same, he has made adjustments to maintain consistency across his five outlets. Instead of using fresh prawns in the stock, he opts for house-made prawn paste.

“The core recipe is the same. Back in the day, you threw in prawn heads. Now I improvise and make my own prawn paste to preserve the freshness (of the ingredient). The freshness of the prawn will not be kept if I were to leave it out for more than a day,” he explained.

Despite modern adaptations, Mr. You Ri believes that a robust broth remains vital to the dish’s authenticity. He notes that many stalls today rely on heavy seasoning to enhance flavour, instead of focusing on improving their seafood broths. “Nowadays, many hokkien mee stalls use a lot of other flavourings to make the taste heavier. It may taste nice, but it no longer tastes like traditional hokkien mee,” he reflected.

“Nowadays, many hokkien mee stalls use a lot of other flavourings to make the taste heavier. It may taste nice, but it no longer tastes like traditional hokkien mee.”

While both versions of hokkien mee share a base of prawn-and-pork stock, their execution tells a story of regional preferences. KL’s rendition is savoury with a slightly sweet and caramelised finish, while Singapore’s version is seafood-forward and umami-packed.

Different dishes, but same key secret

Despite the many differences that set the two dishes apart, they share a key similarity in their cooking process: the use of the wok.

For KL hokkien mee, the wok is only part of the equation. The real magic lies in the charcoal fire. Nothing else can replicate the deep smokiness and complexity it brings to the dish. As Mr. Lee of Petaling Street Charcoal Hokkien Mee puts it: “The charcoal fire brings good smell and good wok hei.”

Image credit: Daniel Chan

Image credit: Daniel Chan

But mastering this charcoal-cooking method is no easy feat. Charcoal fires are notoriously unpredictable—too hot, and the noodles burn in seconds; too weak, and the dish loses its signature smokiness. “The most difficult part is controlling the fire,” Mr. Lee explained. “The charcoal is very hot, so timing is everything.”

Mr. You Ri shared the same sentiment, in that mastering how to control the fire is the most vital aspect of making hokkien mee. He simply stated: “You cannot miss one step (during the cooking process), but most important is the fire.” Based on our hokkien mee article, most of the long-standing hokkien mee hawkers in Singapore reflect this notion.

“You cannot miss one step (during the cooking process), but most important is the fire.”

What Makes Good Hokkien Mee, According To Singapore’s Most Famous Stalls

However, while KL hokkien mee clings to the importance of using traditional charcoal fire, most Singaporean stalls, including Original Simon Road Hokkien Mee, have moved away from this old-school method. These days, gas-fired woks are the norm in Singapore, trading some of that smoky depth for practicality and consistency—even legendary stalls such as the aforementioned Nam Sing have switched to a gas stove.

Different dishes, but appreciated all the same

The story of how KL hokkien mee and Singapore hokkien mee came to be will always be a mysterious one. We know that both dishes were brought to their respective countries by Fujian immigrants, but it seems they were birthed from completely different circumstances, and have developed into truly native dishes of Singapore and Malaysia.

Nevertheless, the two hokkien mee dishes illustrate the distinct culinary cultures of both countries, while also representing the history they share. It is no wonder that they remain iconic in their respective countries to this day.

For more good hokkien mee stalls recommendations, check out our ranking of the best hokkien mee stalls in Singapore to see where some of your favourites stand! Else, check out our The Pine Garden feature to get to know the story behind this famous 40-year-old bakery in Ang Mo Kio!

13 Best Hokkien Mee In Singapore Ranked—Nam Sing, Xiao Di, Geylang Lorong 29 And More

Petaling Street Charcoal Hokkien Mee

Address: 46 Jalan Manjoi, Taman Kok Lian, 51200 Kuala Lumpur, Wilayah Persekutuan Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Opening hours: Wed-Mon 11am to 9pm

Tel: +60 12-295 7279

Petaling Street Charcoal Hokkien Mee is not a halal-certified eatery.

Original Simon Road Hokkien Mee

Address: 339 Anchorvale Road, #02-06, Anchorvale Village Hawker Centre, Singapore 540339

Opening hours: Tue-Sun 8am to 8pm

Website

Original Simon Road Hokkien Mee is not a halal-certified eatery.

Photos taken by Marcus Neo.

This was an independent feature by Eatbook.sg.

Feature image adapted from Petaling Street Charcoal Hokkien Mee.

Top In Asia