SINGAPORE — Young adults who were physically punished as children are far more likely to say they intend to hit their own children in the future, compared with those who were not physically disciplined.

This is one key finding from a new study which sheds light on how corporal punishment is passed down from one generation to the next, led by a psychology professor from Nanyang Technological University.

And this is especially pertinent in Singapore, where such practices remain common.

For example, 88 per cent of the study’s respondents said they were beaten at least once during their childhood by their parents, and 79 per cent grew up with a cane at home. Being caned or hit by their parents’ hands were the most common forms of discipline.

About 450 undergraduates in Singapore aged 18 to 29 were surveyed for the study.

Associate Professor Setoh Pei Pei, who led the study, said: “Caning a child is common in Singapore, though it’s not so common in other countries. It’s what we grow up with and what we think is normal.

“The norms are so strong that we may not really question or reflect: Does it have to be this way? We should take this opportunity to reflect on our approach to discipline.

“Not as a tool for punishment or control, but to guide and teach, and help our children learn the skills they need to make good choices on their own.”

The study also found that children who were harshly disciplined — including being caned, kicked or slapped on the face — and subjected to threats, yelling and other forms of psychological aggression are more likely to be aggressive and have poorer mental well-being.

This is because excessively harsh punishment may strain the parent-child relationship, causing children to feel misunderstood or emotionally alone, Prof Setoh said.

In contrast, the study found that minor forms of discipline, like a smack on the palm or buttocks, were not linked to long-term behavioural issues.

The findings of the study were published in the journals Acta Psychologica on June 3 and Child Protection and Practice on March 7.

The study’s co-authors are Dr Henning Tiemeier, a Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health professor; Dr Yena Kyeong, of the National Taiwan Normal University; Dr Mioko Sudo of the International Christian University; and Won Ying Qing, who is doing her PhD at the University of Melbourne.

The findings include:

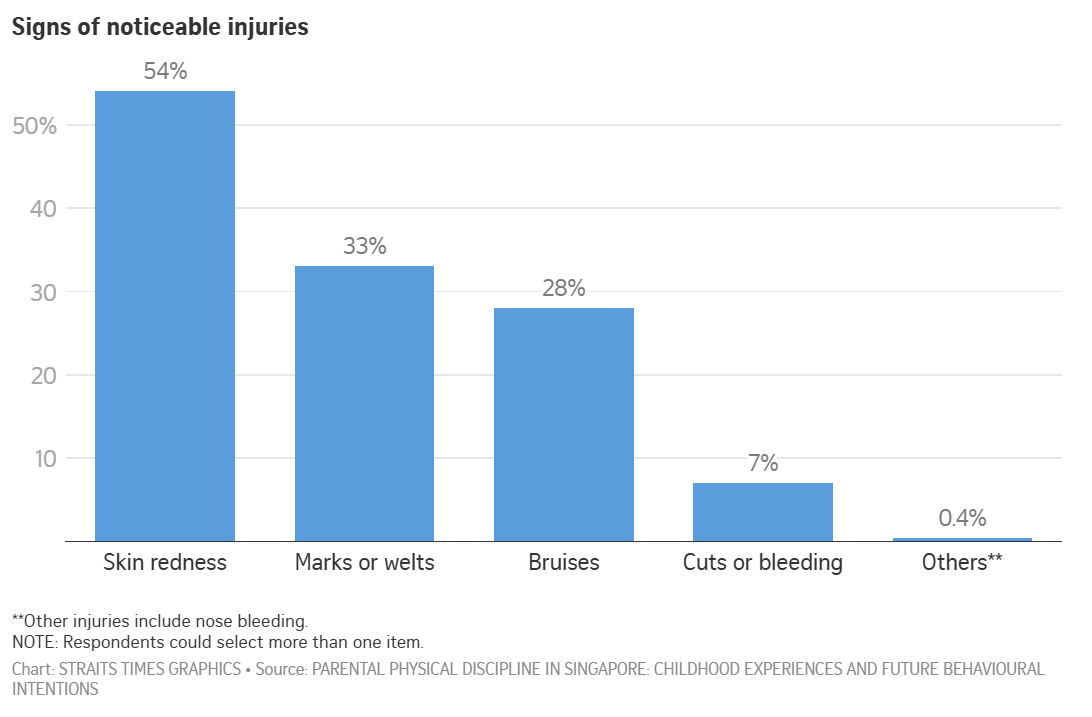

- Of those who were physically punished, 63 per cent saw at least one noticeable injury. The most common injuries were having their skin turn red, marks and bruises.

- 89 per cent of the young adults recalled instances when their parents were not in control of their emotions when punishing them, while about 80 per cent said their parents sometimes felt guilty after beating them.

- 54 per cent said the punishment hurt “quite a lot” or “terribly”.

- 96 per cent said the beatings stopped by the time they were between 15 and 17 years old.

- Of those who were physically punished as children, 59 per cent said they may discipline their future children in the same way too. This is compared with only 26 per cent who indicated they may beat their future children, if they were not physically disciplined during their childhood.

- 71 per cent did not feel that physical punishment should be banned in Singapore. To be clear, there is no law here that bans parents from physically disciplining their children.

Prof Setoh said she was surprised that so many of the young adults who grew up being physically disciplined said they plan to continue such a practice when they become parents.

She said the study is representative of Singapore’s tertiary-educated population. And it offers a snapshot of the attitudes of today’s young adults — and tomorrow’s parents — about corporal punishment.

She added that past research, including one that she was involved in, has consistently showed a high prevalence of parents in Singapore using physical discipline.

She also pointed out that over 100 studies and several dozen meta-analyses done by researchers worldwide show that physical punishment does more harm than good in the long run. A meta-analysis combines the findings of multiple studies to develop a single and more robust conclusion.

She said: “No high-quality research has found long-term positive outcomes for children who experience parental physical discipline.

“The only documented short-term benefit is immediate compliance, which is both fleeting and outweighed by the persistent, reliably demonstrated negative effects on child behaviour, self-esteem, parent-child relationship quality and mental health.”

Spare the rod and spoil the child?

Dr Charlene Fu, the head of the research unit at Singapore Children’s Society, said the findings from Prof Setoh’s study largely align with that from its study conducted in 2021, which polled more than 600 young adults and over 700 parents. For example, young adults told the Singapore Children’s Society that physical discipline strained parent-child relationships and negatively affected their mental health.

Lim Hui Wen, a senior manager at Allkin Singapore’s specialist services division, said physical discipline, particularly caning, has traditionally been seen as a form of tough love or a corrective measure to help children succeed in life.

She said: “When individuals grow up with such practices, they may internalise them as effective or acceptable, especially if they believe they have turned out well under such a parenting style.”

However, Lim cautioned that the line between physical discipline and abuse is a thin one, and it can be crossed in the heat of the moment when emotions run high.

She said: “If a child experiences bruises, emotional or psychological trauma, it is no longer discipline — it is abuse.”

She encourages parents to adopt the principles of assertive discipline, which emphasise clear communication, consistent boundaries, and respectful correction, without resorting to physical or emotionally harmful methods.

Nawal Adam Koay, an assistant director at the Singapore Children’s Society, also encouraged parents to adopt alternative ways to guide their children, instead of using physical discipline.

She recommends the 3R approach, where the first R stands for regulate. This is to help the child to regulate and calm their emotions, so that the child is in a mental state where learning is possible.

The second R is relate, where the parents listen to the child and show empathy, which helps to build trust and allows the child to share their thoughts and feelings.

Finally, the third R is reason.

This is because when the child feels calm and connected to their parents, parents can support them to reflect on their behaviour, learn from it and explore making better choices.

SINGAPORE HELPLINES

- Samaritans of Singapore: 1800-221-4444

- Singapore Association for Mental Health: 1800-283-7019

- Care Corner Counselling Centre (Mandarin): 1800-353-5800

- Institute of Mental Health’s Mental Health Helpline: 6389-2222

- Silver Ribbon: 6386-1928

- Shan You Counselling Centre (Mandarin): 6741-0078

- Fei Yue’s Online Counselling Service: www.eC2.sg

- Tinkle Friend (for primary school children): 1800-2744-788

[[nid:718823]]

This article was first published in The Straits Times. Permission required for reproduction.

Top In Asia